Memorandum on the 1994 Assassination of

Juvenal Habyarimana, President of the Republic of Rwanda

English Translation- December 1999 – Original published in French in July 1999

In collaboration with Organization for Peace, Justice and Development in Rwanda (OPJDR)

Felicien Kanyamibwa, Ph.D.

Email: kanyami@optonline.net

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. Introduction

2. History

3. Climate – Spring 1994

3.1 Burundi

3.2 Uganda

3.3 Invasion of Rwanda

3.4 Assassinations in Rwanda

3.5 The Arusha Accord

3.6 Warning Signs

3.6.1 The RPF Battalion

3.6.2 The RPF and the air traffic Corridor

3.6.3 Meeting of the final preparation

3.6.4 Delay Tactics

3.6.5 Dallaire’s Question

3.6.6 Regional Summit of Heads of State on Burundi

4. The Missile Attack on President Habyalimana’s Plane

4.1 The Night of the Assassination

4.2 Different Reactions after the Assassination

4.2.1 Inside Rwanda

4.2.2 Rwandan Patriotic Front

4.2.3 UNAMIR

4.2.4 President Museveni and His Army

4.2.5 The Tanzanian Government

4.2.6 Government of Burundi

5. Regarding the Arsenals Used to Shoot Down the Plane

6. Possible Suspects

6.1 The Burundese Connection

6.2 The Moderate Opposition

6.3 Hutu “Extremists” from the Former Rwandan Government

6.4 The Rwandan Patriotic Front, with Assistance from its Foreign

Allies

6.4.1 Motive

6.4.2 The Plan to Remove Habyiramana

6.4.3 The Means to Shoot the Presidential Plane

7. The Investigation

7.1 The Interim Government

7.2 The RPF Government

7.3 The United Nations Organizations

7.4 Organization of African Unity

7.5 The Belgian Government

7.6 The French Government

7.7 The American Government

7.8 International Civil Aviation Organization

8. Call for an Independent Investigation

8.1 The Trigger Event of the Rwandan Tragedy

8.2 Need for Justice and Fairness

9. Conclusions

10. Abbreviations

1. Introduction

In April of 1994, the small, central African country of Rwanda broke out into an

uncontrollable civil war when hostile missiles shot down its president’s airplane. The

chaos that followed created headlines around the world throughout that summer. The

world was stunned by the violence perpetuated by what the media consistently referred to

as normally peaceful people. Because the shooting of the plane was the trigger that

spiraled Rwanda into chaos and civil war, in order to understand what happened, it is

important to know who triggered these events, and why. However, there has been no

investigation conducted by the UN to uncover the identity of the perpetuators of the

sabotage of the presidential plane. In order to pursue peace and reconciliation in

Rwanda, those who shot down the plane must be revealed and held accountable.

2. History

In order to understand the significance of the events surrounding the downing of

President Habyarimana’s airplane on April 6, 1994, it is crucial to have at least a

fundamental understanding of Rwanda’s history. Rwanda’s population traditionally

consisted of 85% Hutu, 10% Tutsi, and 5% Twa. For nearly four hundred years, Tutsis,

members of the minority ethnic group, headed by a Mwami (king) ruled the majority of

the Hutu ethnic group. The Hutus were treated as “peasants”, and did all of the manual

work. Colonialists (Germany and later Belgium) accepted the status quo, and did not try

to change the fundamental structure of Rwandan society. In early fifties, Hutus began

demanding a better representation in the governing institutions. This led subsequently to

the 1959 social revolution which was accompanied by fighting between the two ethnic

groups. Consequently, an estimated 100,000 Tutsis fled to neighboring countries

including Burundi, Congo, Uganda, and Tanzania. Bloodshed and violence was rampant

during this period. In 1962, Rwanda became independent under their new president,

Gregoire Kayibanda. The latter was member of the Hutu ethnic group. For the first time,

Hutus were permitted to obtain secondary and post-secondary education.

In 1973, a coup established Maj. Gen. Juvenal Habyarimana as the new president

Habyarimana who started a relatively peaceful era. Under his rule,Tutsis enjoyed peace

and economical prosperity. It should be noted though, that Habyarimana did not allow

those Tutsis who had fled during the wake of 1959 social revolution to return massively

to Rwanda. The reason put forward was that the country was too small to accommodate

such massive return. In fact, Rwanda is one of the most overpopulated countries in the

world. However, this created tension, and those exiled Tutsis felt, perhaps justifiably, that

they should have had the right to return to their homeland. Meanwhile within Rwanda,

ordinary Hutus and Tutsis went to school together, went to church together, worked side

Assassination of Juvenal Habyarimana, President of the Republic of Rwanda

by side, and helped build up an infrastructure that was the envy of that whole region of

Africa.

3. Climate – Spring 1994

In the spring of 1994, when Habyarimana’s plane was shot down, things had become very

tense. The peace, which the country enjoyed since 1973, had become increasingly

fragile, and, by April, Rwanda was like a tinder-box into which the deliberate death of the

president was like someone throwing a match. In order to understand what had created

these new conditions, it is important to look at the political climate of the time, and at

what had taken place in the years prior to 1994.

3.1 Burundi:

Events in neighboring Burundi undermined Hutu/Tutsi relations in Rwanda. Burundi has

a similar ethnic makeup as Rwanda, with 10% Tutsi and 90% Hutu. Burundi gained its

independence in 1962, but was mostly ruled by a military republic. They were not able to

achieve peace between the two tribes. During the 1970’s there were thousands of Hutu

deaths, and again, after a military coup in 1987, there were more serious ethnic clashes.

An example of this, is that in 1972 and 1988, Tutsi soldiers in Burundi’s Tutsi dominated

army, went into the public schools, separated the children by tribe, and massacred all of

the Hutu children in each school that they visited. In 1993, the first democratically

elected Hutu president, Melchior Ndadaye, was elected in Burundi. However, in October,

1993, he was assassinated by the monoethnic Tutsi army. This assassination was

regarded by Hutus in Rwanda as a clear indication that the Tutsi minority in Burundi had

the intention of preventing democracy there. Rwandan Hutus did not only have to look to

the past to remember the oppressive rule of the minority Tutsi tribe, they only had to look

at their neighbor to the South to see and fear the oppression which they had escaped in

1959.

3.2 Uganda:

The exiled Tutsi’s whom Habyarimana had not permitted to return to Rwanda, had

largely established themselves in Uganda, the country to the north of Rwanda. They had

helped Uganda’s current president, Yoweri Museveni, depose Present Okello in 1986.

President Museveni was then in the position of owing this group a favor. This group was

mostly composed of Tutsis who fled Rwanda after the 1959 social revolution. This group

of Tutsis in Uganda formed the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), and, on October 1, 1990,

invaded Rwanda across the northern border, killing and torturing men, women and

children who lived in villages along that border.

3.3 Invasion of Rwanda:

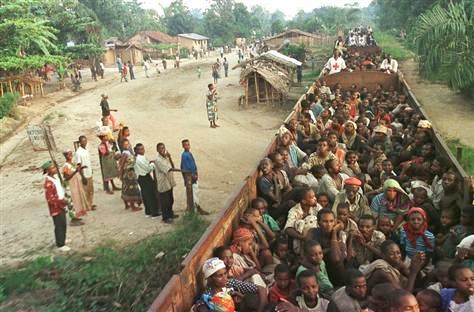

As mentioned above, the exiled tutsis who formed the bulk of President Museveni’s army

invaded Rwanda on October 1, 1990. Members of the RPF used Uganda as a base from

which they launched all their attacks on Rwanda. These raids were notorious for their

carnage and cruelty. By 1993, there were an estimated one million Hutu villagers fleeing

these Ugandan-based raids by fleeing towards the interior of Rwanda. At that time, the

population of Rwanda was approximately seven million. This means that, in the spring of

1994, one in seven people in Rwanda were refugees in their own country. Western media

predicted a widespread famine in Rwanda that year due to this large displaced population.

This too, of course, created tension in Rwanda, particularly in the northern area, where

the RPF was attacking from, and where, as a consequence, there was increasing tension

between the local Hutus and Tutsis.

3.4 Assassinations in Rwanda:

-In 1993, Emmanuel Gapyisi, a member of the political bureau of MDR, President of

MDR in Gikongoro, and an active member of a group called “Forum Paix et Democratie”

was assassinated.

-The same year, Fidele Rwambuka, a member of the National Committee of the

Republican National Movement ofr Democracy and Development (MRND), was also

assassinated.

-On February 21, 1994, Felicien Gatabazi, who was both the Executive Secretary of the

Social Democratic Party (PSD) and a member of the Rwandan coalition government, was

gunned down at the entrance of his house.

-The following day, February 22, 1994, Martin Bucyana, the President of the Coalition

for the Defense of the Republic (CDR) was assassinated in Butare. There were strong

presumptions among the public that these political assassinations were committed by the

RPF. It is a well known fact that all of these hutu leaders had been opposed to the RPF

and committed to the victory of democracy and republican ideals. There were strong

presumptions among the public that these Hutu leaders were killed by RPF death squads.

Their murders exacerbated differences among political parties, and added to the mistrust

and tension throughout the country.

3.5 The Arusha Accord:

In order to come to a lasting peace, President Habyarimana negotiated a peace accord

with the RPF and various factions of his government. This accord guaranteed the Tutsi

minority a percentage of seats in government within a power sharing arrangement in

running the government. It was controversial, because many Hutus felt that Habyarimana

had given too much to the 10% minority, while members of the RPF did not desire the

full implementation of the agreement because it guaranteed that they would never have

the total control on the governmental affairs. The UN sent on November 1, 1993 a

mission to Rwanda known as the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda

(UNAMIR), to assist in the transition.

3.5 Warning Signs

A document called “Environnement actuel et avenir de l’organisation” outlines an

apparent scenario designed by RPF ideologues and strategists shortly after the signing of

the Arusha accord. The plan was to evict Habyarimana within nine months. A review of

the events following the signing of the agreement seems to support the existence of a

calculated intention to oust Habyarimana.

3.5.1 The RPF Battalion:

On July 20, 1993 in Kinihira, the RPF had requested and obtained the installation of a

battalion in the capital, Kigali. The purpose of this battalion of 600 soldiers was

theoretically to protect RPF officials. This battalion was housed in the building of the

National Council for Development (CND), the Rwandan National Assembly, a strategic

site in the center of Kigali. The RPF requested that all supplies (even wood) be brought

in from Mulindi (territory under RPF occupation). When supplies were coming from

Mulindi, the RPF refused to submit to control at the check point of the territory controlled

by the Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR). Security feared that they could be bringing in

extra weapons and soldiers, but were unable to prevent it without the cooperation of the

RPF. The Belgian contingent of UNAMIR in charge of escorting these convoys

supported the RPF’s refusal to be checked. The matter was brought to the attention of the

commander of the UNAMIR, General Dallaire, but nothing was done about it.

Later events would confirm that those convoys had indeed helped in smuggling military

equipment and additional reinforcement to the RPF battalion in Kigali, and that the

battalion itself had played the role of a Trojan horse1. Evidence strongly points to the fact

that these supply convoys probably brought in the missiles used to shoot down the

presidential plane. General Dallaire was apparently informed about the existence of these

missiles, but did nothing about them2.

3.5.2 RPF and the air traffic corridor:

In January 1994, the RPF requested that landing approach and take-off at Kanombe

International Airport be prohibited from the downtown corridor of Kigali. It argued that

1 Jacques Bihozagora, a member of the RPF government, later confirmed this analysis on a round table

program broadcast by Radio Rwanda on the anniversary of the eve of the capture of Kigali. He declared

that the battalion’s mission was to “liberate the capital”. Furthermore, Ntaribi Kamanzi, an RPF journalist,

revealed in his book “ Rwanda. Du Génocide à la Défaite”, how two battalions (1200 soldiers selected

from all APR units) had been prepared for urban operations before being sent to Kigali. That is twice the

number who were agreed upon to be in that battalion at the time. Ntaribi Kamanzi in “Du Génocide à la

Défaite” p. 69.

2 Report of the Belgian Parliamentarian Commission for Rwanda, (COM-1-9)

airplanes using this corridor were flying over its military contingent, and therefore, its

security was at risk. In a bold pressure tactic on the government, the RPF battalion

housed in CND actually shot at a Belgian transport airplane, a C130 Hercules,

approaching Kanombe International Airport from downtown Kigali. The plane was not

hit. Although this action clearly contravened the Arusha Peace Accord, The UNAMIR

intervened and pressured the Rwandan government to yield to the RPF request. Finally,

the government gave in and agreed to change the permitted flight approach to the airport.

In retrospect, it appears that this was a tactical move to make it more possible to shoot

down the presidential airplane three months later. It was now possible to shoot at the

plane from one side, Masaka, a rural, covered area with little control3.

3.5.3 Meeting of the final preparation:

It is reported that in March 1994, RPF strategists met in Bobo-Diuolasso, Burkina Faso.

Manzi Bakuramutsa, an employee of the UN Development Program (UNDP), a Zairian

citizen at the time, arranged the meeting. During this high level meeting, the last details

of the plan to physically eliminate President Habyarimana were agreed upon. After its

victory, the RPF appointed Manzi Bakuramutsa ambassador of Rwanda to the UN. He

later served as ambassador to Belgium. Today, he is ambassador to Israel.

3.5.4 Delay Tactics:

On March 25, the RPF refused to attend the inauguration ceremony of the remaining

institutions of the transition. Delays and refusal to cooperate with the implementation of

the Arusha accord followed. Arguing over candidates of other political parties, on

grounds that could not be supported by the Arusha Accord, they significantly delayed the

implementation of the peace accord. Ntaribi Kamanzi recalls this situation in his book

mentioned earlier. He says that when western diplomats based in Kigali went to Mulindi,

the RPF headquarters, in March 1994 to try to persuade the RPF to change its position, a

western diplomat expressed to them his disappointment at their refusal to cooperate4.

While these delays and “foot-dragging” do not in themselves appear significant, they can

be seen as important when viewed from a historical perspective. It is important to note

that while there were opponents to the Arusha Accord on both sides, it was the RPF

contingent that was delaying its implementation. Perhaps they believed that once the

accord was successfully implemented, they would have no justification in the

international forum to wrest the control from the current administration. A logical,

tactical strategy, therefore, would be to delay and sabotage the transition long enough to

3 Refer to the letter of the Falcon 50 Pilot, Appendice of the Mission d’Information Parlementaire

Francaise.

4 Ntaribi Kamanzi in “Du Génocide à la Défaite” pp. 77-78

gain full control of the country without international outrage at replacing a democracy

with military rule. A 10% minority, of course, cannot rule by democracy.

3.5.5 Dallaire’s Question:

On April 3, 1994, the Representative of the UN Secretary General, Roger Booh Booh,

informed President Habyarimana that, according to diplomatic sources, the RPF planned

to assassinate him. The UNAMIR was then informed of the plot to assassinate the

President. The next day, two days before the assassination, during a reception at Hotel

Meridien, General Dallaire asked a rather strange question of Ret. Col. Theoneste

Bagosora. He asked; “Who is the designated successor to President Habyarimana?”

Bagosora replied that he did not know. Although clearly warned of the plot, no apparent

action was taken by General Dallaire and the UNAMIR to prevent the assassination.

Dallaire merely inquired as to the successor.

3.5.6 Regional Summit of Heads of State on Burundi:

On April 6, 1994, the President went to Dar-es-Salaam for a regional summit of Heads of

State on Burundi. There were many warning signs that this summit was a trap. The

summit, originally called to discuss the situation in Burundi, discussed Rwanda’s

situation instead. Its final communiqué has not been published to this day. It was

originally scheduled to be held April 5, 1994, in Arusha, and then was postponed to take

place on April 6 in Dar-es-Salaam. Some of the scheduled participants did not show up

for the summit. Why was the summit called, if it was not significant enough to stay on

the agenda, and to publish its results? Why the changes in agenda, time, place, and

participants? As it was upon flying home from this summit that President Habyarimana’s

plane was shot down, perhaps the answers to these questions will help shed light on that

fateful assassination.

The summit ended later than previously scheduled mainly because of Uganda’s President

Museveni. First, he arrived in Dar-es-Salaam very late. Then, the meeting that was

begun late was unusual. President Museveni slowed down the meeting using multiple

and intemperate digressions. President Habyarimana and President Ntaryamira of

Burundi signed the final communiqué at the airport just before embarking. They had

asked to spend the night in Dar-es-Salaam, as their pilot had expressed concern for their

safety on a late flight. However, President Mwinyi, their Tanzanian counterpart, had told

them that no measure had been taken to have them spend the night. They had no choice

but to fly home that night, later than planned, in the dark, and with concerns for their

safety. Despite all of these last minute changes, out of the control of the Rwandan

president, and their later than expected departure, caused in large part by Museveni,

President of Uganda, their assassins were somehow expecting them, waiting in the dark,

on a hillside (on the new air traffic corridor) outside Kigali.

4. The Missile Attack on President Habyarimana’s plane

4.1 The Night of the Assassination:

The airplane with a French crew took off from Dar-es-Salaam Airport at approximately

6:30 PM Kigali time, with the Rwandan and the Burundian delegations aboard.

The Rwanda delegation included:

1. President Juvenal Habyarimana

2. Major-General Deogratias Nsabimana, Chief of Staff of the Rwandan Army

3. Ambassador Juvenal Renzaho, adviser in the President’s Office

4. Colonel Elie Sagatwa, the President’s Private Secretary

5. Doctor Emmanuel Akingeneye, the President’s doctor

6. Major Thaddee Bagaragaza

The Burundian delegation included:

1. President Cyprien Ntaryamira

2. Secretary Bernard Ciza

3. Secretary Cyriaque Simbizi

The French crew included:

1. Major Jack Heraud

2. Colonel Jean-Pierre Minaberry

3. Master Sergeant Jean Marie Perrine

At approximately 8:20 PM, local time, the presidential jet was shot down with missiles

fired from a farm located in Masaka in the commune of Kanombe, near the Kigali-to-

Kibungo highway. Of the two missiles shot, one hit the plane. By strange coincidence,

the plane crashed into the courtyard of President Habyarimana’s private residence. All

passengers and crew died immediately.

Earlier that day, a group of soldiers, members of the Belgian contingent led by Lieutenant

Lotin went to the eastern part of the country, the Akagera National Park, to escort RPF

officials. This group of soldiers returned to Kigali in the evening and was given the

assignment to escort Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana to Radio-Rwanda where she

intended to address the nation. It is this group of soldiers who were killed in the military

barrack of Kigali by mutineers on April 7, 19945.

5 Alexandre Goffin published this information in his book “Rwanda 7 Avril 1994: 10 commandos vont

mourir”, page 23. Colonel Luc Marchal and Lieutenant Colonel Dewez, commander of KIBAT later

confirmed it before the Belgian Parliamentary Commission for Rwanda: Report of the Belgian

Parliamentarian Commission for Rwanda, (COM-R-1-15 & 1-72).

4.2 Different Reactions After the Assassination

After the assassination, RPF propagandist and its sponsors spread a story that President

Habyarimana died in an accident. General Dallaire’s statement to this effect led to

confusion and speculation. Dallaire knew that missiles had shot down the airplane.

When RPF propagandists realized that this story would not bear up to scrutiny, they

declared that the President had been killed by Hutu extremists, among them members of

the Akazu (a circle of influential relatives around the President), including Habyarimana’s

wife. Later on, many observers acknowledged that the so-called “Hutu extremists” did

not have the means or the interest in carrying out the assassination. They then suggested

many possible hypotheses. An analysis of different reactions points to serious clues as to

who conducted the assassination.

4.2.1 Inside Rwanda:

On April 6, 1994 around 9:15 PM Radio RTLM announced without any detail that the

presidential jet had been shot down, and promised to provide further information in later

broadcasts. At this time, the death of the President was not confirmed. Radio-Rwanda

announced the President’s death the next morning at 5:30 AM in a communiqué issued by

the Ministry of Defense. In general the population of the capital reacted with anger and

panic. However, some RPF sympathizers could not restrain their joy.

An impromptu meeting including officers of the army and the gendarmerie, the Ministry

of Defense, the military barrack of Kigali, General Augustin Ndindiliyimana, Chief of

Staff of the Gendarmerie, and Ret. Col. Theoneste Bagosora, Chief of Staff of the

Ministry of Defense took place at the headquarters of the Rwandan Army on April 6,

1994. The meeting started around 10:00 PM and went on through the night. General

Dallaire, the UNAMIR Commander and Colonel Marchal, head of the Belgian contingent

participated in this meeting. The purpose of the meeting was to take security measures to

prevent possible violence, reassure the population, and preserve peace in this situation of

power vacuum. After this meeting a delegation including Ret. Col. Bagosora and Colonel

Rwabalinda went to meet the Representative of the UN Secretary General, Roger Booh

Booh to seek his advice about how to manage the crisis. General Dallaire accompanied

the delegation.

A meeting, which was suggested by Booh Booh at the US ambassador’s residence, and

which was supposed to include western ambassadors, General Ndindiliyimana, and

Colonel Bagosora did not take place. Only the US ambassador showed up for the

meeting. Others western ambassadors did not show up at the place designated for the

meeting.

As agreed upon during the meeting held the night before at the headquarters of the

Rwandan Army, a meeting of the heads of the Rwandan Armed Forces (the Chief of Staff

of the Gendarmerie, the Chief of Staff of the Ministry of Defense, military officers

assigned to the headquarters of the army and the headquarters of the gendarmerie, field

commanders, commanders of the barracks of the gendarmerie and the army) was held at

the military academy of Kigali. General Dallaire participated in this meeting as well.

This meeting set up a crisis committee with a mission to facilitate contacts with political

leaders in order to fill the power vacuum created by the tragic death of the head of state

and to monitor the security situation in the country.

On the same afternoon, following recommendations made by the Representative of the

UN Secretary General, Roger Booh Booh, the executive committee of MRND held a

meeting. The meeting had been suggested to find a replacement for the President.

However, participants ran into two obstacles: the first obstacle was that the Arusha Peace

Accord did not provide for a replacement of the President before the inauguration of the

institutions of the transition; the second obstacle was that only an MRND convention

could designate a candidate to the Presidency of the Republic. A second meeting became

necessary to overcome these obstacles. This second meeting took place on April 8, 1994.

Representatives from 5 political parties, members of the coalition government (MRND,

MDR, PL, PSD, PDC) participated in this meeting. This meeting concluded an

agreement that supplemented the Convention signed on April 16, 1992. Indeed, on April

8, 1994, Theodore Sindikubwabo, President of the National Assembly (CND) was

designated President of the Republic as provided by the Constitution of June 10, 1991,

and Jean Kambanda was designated Prime Minister. The Interim Government was sworn

in on April 9, 1994.

4.2.2 Rwandan Patriotic Front:

Immediately after the assassination, the RPF battalion housed in CND in Kigali rejoiced

and shouted “final victory”. The headquarters of the RPF at Mulindi was immediately

informed of the death of the President. In his book mentioned above, Ntaribi Kamanzi

says that the RPF battalion housed at CND sent a message announcing the death of the

President to the RPF headquarters at Mulindi around 8:30 PM, just after the

assassination. The same night, in the wake of the assassination, General Kagame made a

declaration of war on Radio Muhabura, the RPF radio station. Around midnight, the

monitoring service of the FAR intercepted a radio message carried by the RPF radio

communication network. In this message, General Kagame informed all military units of

his army of the death of the President, congratulated all the military that had participated

in the assassination, and put on high alert all military units.

On April 7, 1994, the RPF initiated attacks in the capital, Kigali and in northern Rwanda6.

The capital plunged into chaos and panic following the death of their president and the

attack by the RPF. It is in this context that mutineers murdered Prime Minister Agathe

Uwilingiyimana and ten Belgian UNAMIR soldiers, believing them to be involved in the

missile attack on the presidential jet. On the afternoon of April 7, Rwandan Armed

Forces (FAR) responded to RPF attacks carried out on all military fronts, and in Kigali,

the capital city. The tragic civil war had then begun.

4.2.3 UNAMIR:

The group of soldiers led by Lieutenant Lotin had returned from a mission in Eastern

Rwanda and was at Kanombe International Airport. It was ordered to protect Prime

Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana and to escort her to Radio-Rwanda to the nation. It is

important to point out that this mission had not been discussed at the meeting held at the

headquarters of the Rwandan Army and in which General Dallaire had participated.

Colonel Marchal confirms this information.

4.2.4: President Museveni and His Army:

On April 7, 1994, the day after the assassination, during the opening of an international

conference held in Kampala, President Museveni could not conceal his satisfaction and

complicity in the assassination. Speaking briefly of the death of President Habyarimana,

he boasted of a mission well done these terms: “It was time to solve the matter.”7

It is not a secret that the Ugandan army actively participated in the major offensive and

provided the RPF with logistics. Estimates say that more than 30,000 Ugandan troops

participated in Rwanda’s “civil” war. President Museveni himself acknowledged

Ugandan army involvement at a summit held in Harare, Zimbabwe on August 9, 19988.

4.2.5 The Tanzanian Government:

When President Habyarimana left Dar-es-Salaam, Capital City of Tanzania in the

evening of April 6, 1994, he left members of his delegation who were supposed to return

to Kigali the next day aboard two Rwandan airplanes (a military North Atlas airplane and

a Twin-Otter of Rwandan Airlines) stationed at the Dar-es-Salaam airport. Without any

6 In fact, in northern Rwanda, the movement of RPF units started before the assassination of the President

and in the capital infiltration originating from the CND intensified in the night of April 6 and April 7, 1994.

On April 8, 1994 RPF troops moving from Northern Rwanda were already in Rutongo (about 7 miles from

Kigali).

7 Africa International No. 272 May 1994, p.7

8 East African Alternatives March/April 1999, p.38-42

explanation, the Tanzanian government did not allow these airplanes to take off from the

Dar-es-Salaam airport. The Rwandan delegation could not return to Kigali. These

airplanes were handed over to Rwanda after the victory of the RPF. Some passengers and

crew members went back to Rwanda, others went into exile.

Even though Habyarimana was assassinated as he was returning from Tanzania, the

president of Tanzania did not send a message of condolences to the people of Rwanda.

This looks particularly significant when one considers that it was he who denied

hospitality to the President when Habyarimana had been concerned about the safety of a

night flight home. Both acts are especially peculiar when one considers that they are not

in line with the african tradition. One cannot help but question his involvement and

motivations.

4.2.6 The Government of Burundi:

Burundi leaders’ attitude towards this assassination is strange. Burundi lost its president,

Cyprien Ntaryamira, and two secretaries in the airplane crash but the Burundese

government reacted to this drama with indifference.

5. Regarding the Arsenals Used to Shoot Down the Plane

After the assassination, the perpetrators left two containers of missile launchers in an

embankment before vanishing. These containers were found on April 25, 1994 by

internally displaced populations, who were resettling in the area (people fleeing from the

violence on the Northern border), and were handed over to the Rwandan Armed Forces

(FAR) the same day.

The FAR had no doubt that the material found on the scene of the crime was what had

been used to perpetrate the assassination. Even though they were not familiar with the

material, it was apparent that the missiles were made in the Soviet Union. The containers

of the missile launchers had a green army Khaki color with the detailed inscriptions.

The inscriptions on the first launcher container are as follows:

9 il322-1-01

9M313-1

04-87

04835

C LOD COMP

911519-2

3555406

The inscriptions on the second launcher container are as follows:

9 il322-1-01

9M313-1

04-87

04814

C LOD COMP

911519-2

5945107

Engineer Lieutenant Munyaneza, a FAR officer, recorded these inscriptions. The missile

launcher containers are significant because they are the only concrete evidence left by the

assassins.

Despite the discovery of the arsenal used to shoot down the plane, and the detailed

inscriptions being immediately recorded, there has been a lot of confusion regarding the

origin and type of missile, and even whether there was indeed a missile attack at all.

Despite the evidence of the wreckage and the discovered arsenal, western media persist in

referring to the downing of the plane as a “mysterious plane crash”. The tracing of the

origin, type, and requisition of the missiles very directly implicates the perpetuators of

the assassination. It is no small wonder that a great deal of misinformation has been

generated around the existence and origin of the weapons used to shoot down the

President’s airplane.

Lieutenant Engineer Munyaneza, who studied engineering in the former USSR, was able

to positively identify the arsenal discovered as missile launchers from the USSR. The

Lieutenant translated and described in detail all relevant information from those arsenals

in a report written on April 25, 19949. Despite this report, written less than three weeks

after the shooting of the plane people have continued to create confusion about this

arsenal.

In his book, “Rwanda: Trois Jours qui on fait basculer l’Histoire”, Professor Reyntjens

alternates terms in describing the arsenal discovered in the farm in the Masaka farm.

Sometimes referring to “missiles”, sometimes “missile launchers”, and sometimes to

“containers” 10. The arsenals that were discovered are not missiles, but containers that are

at the same time missile launchers. In fact, for this type of arsenals, the missile and the

launcher are delivered as one piece and once the missile is fired, the launcher, which

holds the missile becomes a useless container. Obviously, the arsenals discovered did not

have the missiles with them because they had already been fired. It is very clear that

information described on the container is consistent with the missiles utilized to shoot

down the presidential jet. Hence, it is more appropriate to describe the arms that were

9 Appendix of the Mission d’ Information Parlementaire Francaise. p. 265

10 Appendix of the Mission d’Information Parlementaire Francaise p. 256

utilized to commit the crime as missiles and the two arsenals discovered at MASAKA as

the missile launchers. This clarification is therefore necessary and important to remove

any confusion regarding terms utilized to describe the arms that shot down the plane.

A more serious confusion than simple terminology is based upon Professor Reyntjens’

book. This is the confusion regarding the type of missile fired. Without demonstrating

how he came to the conclusion, Professor Reyntjens states: “All we can say with

certitude is that it is a missile of type SAM-16 Gimlet.”11 He maintained this assertion

before the Belgian Parliamentarian Commission for Rwanda without demonstrating any

evidence to his conclusion.

Later, in his letter to the Chairman of the Mission d’Information Parlementaire Francaise,

he attested that the Rwandan Armed Forces, and particularly Ret. Col. Bagosora,

provided the information to him, telling him that the arsenals were of Type SAM-16

Gimlet. As far as we know, the Rwandan Armed Forces, as well as Ret. Col. Bagosora,

have always maintained that they discovered missiles of type SAM-7 and never said they

were missile type SAM-16 Gimlet. Ret. Col. Bagosora sent Professor Reytjens, through

his lawyer, Mr. Luc de Temmerman, a copy of the document written by Lieutenant

Engineer Munyaneza. This document does not talk about missiles or type of missiles at

all but mentions instead missile launchers. The copy sent by Ret. Col. Bagosora is

exactly the same as the one that was cited in documents referred to by the Mission

d’Information Parlementaire Francaise12. Adding to the confusion by basing their

information on Professor Reyntjens’ work, the French commission shows a photograph of

a missile launcher (type SAM-16 Gimlet), and affirms that witnesses who found the

missile launcher identified the picture as being the same as the one discovered on the

farm on Masaka13. However, farmers and people who uncovered the arsenal at Masaka

consistently deny the French commission picture as being authentic.

The confusion between the types of missile is important because the Ugandan army, the

established arm suppliers of the RPF, did not have any type SAM-16, and had only type

SAM-7. Although all evidence, witnesses and inscriptions, point to the fact that the

missiles fired were type SAM-7, Professor Reyntjens maintains that the missiles were

type SAM-16, and uses this evidence to exonerate the RPF of the assassination: “ the

missiles belonging to the RPF, were coming most probably from the Ugandan Army

inventory; however, the latter has only SAM-7, and not SAM-16, most likely utilized to

shoot down the plane14.” Another writer, Colette Braeckman, also ignores witnesses and

11 Philip Reyntjens. “Rwanda. Trois jours qui ont fait basculer l’Histoire” p. 45

12 The Mission d’Information Parlementaire Francaise. T II, annexes, p. 265

13 Appendix of the Mission d’Information Parlementaire Francais p. 265

14 Letter of Philip Reyntjens of December 10, 1998 to Mr. Bernard Cazeneuve, Chairman of the Mission

d’Information Parlementaire Francaise, included in the appendices of the Report.

17

serial inscriptions to draw her own conclusions about the type of missile used:

“Regarding, the assassination attempt itself, it was confirmed that it was a well prepared

military operation, carried out by specialists of high flights and that the arsenal used has

probably been a mobile SAM missile of serial Strela.”15 Both conclusions are not

factually based, and are used to exonerate the RPF from the assassination of President

Habyarimana.

The confusion used in shooting down the presidential jet still persists. It runs a risk of

misleading any future investigation. One would maintain that only a logical fact-finding

mission, based on eyewitness accounts, and the inscriptions recorded, conducted by

ballistic experts, should be able to draw conclusive results.

6. Possible Suspects

Professor Reyntjens, the Mission d’Information Parlementaire Francaise, and the Belgian

Parliamentarian Commission for Rwanda all investigated the assassination, and all

developed lists of who could be behind the shooting down of the presidential jet. Each

developed a list of suspected groups who could have the motive to get rid of

Habyarimana. While the wording of each is different, the groups are fundamentally the

same. The four possible suspects are:

1. The Burundese connection;

2. Moderate opposition; the democratic coup that went horribly wrong, possibly

with the help of the RPF;

3. Hutu extremists from the former Rwandan regime, working with the army, and

possibly the help of French operators;

4. The Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), with assistance from the Belgian military

Each investigation leans more heavily on various information, and none succeeds in

coming to a convincing conclusion. The result of these investigations is a sense of

further confusion. At this point, it is important to take a step further by putting all these

hypotheses together and to proceed by eliminating improbable hypotheses that are

essentially misleading.

6.1 The Burundese Connection:

Regional experts, as well as both commissions quoted above, have disqualified the

Burundian lead. We think that their analysis and results are absolutely correct.

6.2 The Moderate Opposition:

15 Colette Braeckman, “Rwanda. Histoire d’un Génocide” p. 196

No one among the moderate opposition has yet demonstrated motivation or technical

ability to conduct such an operation. Furthermore, key players in the opposition, such as

Mr. Faustin Twagiramungu, the designated Prime Minister, have expressed their strong

views regarding the assassination issue16. Regarding the possibility of a conspiracy

between the RPF and the opposition, the latter would almost certainly have been led by

the RPF and not the other way around. This would lead us back to hypothesis #4, which

shall be reviewed shortly.

If we eliminate the first two hypotheses, we are left with two main possibilities: the Hutu

“extremists”, and the RPF. These are the two main leads upon which most opinions tend

to agree. In investigating which of these groups may have done the assassination, the

most relevant questions to be asked are: “Who benefits from the crime?” 17, and “Who

had the means to carry out the assassination?”. In other words, it is important to

determine who had the means and the motive.

6.3 Hutu “Extremists” from the former Rwandan Government:

Did the closest people to President Habyarimana have any interest to kill him? Nothing

is sure. Detractors of Habyarimana and his entourage seem to believe that his closest

allies, who wanted to remain in power, because they feared losing their privileges, may

have killed him. Was the death of Habyarimana itself a guaranty to remain in power and

keep their privileges? Their detractors believe the answer is yes. The President

supporters affirm that Habyarimana had given up many concessions that Hutu extremists,

as well as his closest people, could neither accept nor tolerate. According to this analysis,

Habyarimana was killed to avoid handing the power to the RPF.

This hypothesis is not supported by the facts and chain of events before and after the

signature of Arusha peace accord. In fact, the alliance between RPF and the Democratic

Forces for Change (DFC) had been severely damaged after many confrontations, mostly

resulting from the hegemonic behavior of the RPF that had reached its critical phase after

16 Declaration of Faustin Twagiramungu before the Mission d’Information Parlementaire Francaise

17 It is curious to see how most analysis done on this topic and many testimonies that have had large

audiences didn’t highlight this question. Of the reports from various sources, such as the one from Rene

Degni Segui, Special envoy of United Nations Human Rights Commission, from experts of United Nations,

from Belgian Parliamentarian Commission for Rwanda, from the Mission d’Information Parlementaire

Francaise or numerous individual opinions expressed publicly here and there, or books written in a rush,

none has conducted a deep analysis with regards to whom this assassination may have benefited.

Some have made reserves in drawing conclusions regarding the author of the crime, hinting that they knew

who it was (Rene Degni Segui, the experts), others have drawn some ambiguous conclusions (Belgian and

French Commissions referred to above), others have tried to push the analysis to the RPF lead without

expressing an explicit opinion (Philip Reyntjens), others have finally mad the decision to put the crime on

the backs of the Hutus without any prior research or analysis (Alison DesForges).

the 1993 offensive. A large number of people from the DFC had come to believe that the

main goal of the RPF was essentially using DFC as a stepping-stone18 to achieve its

objective of gaining total political power. The great majority of the opposition had then

switched their alliance. This did not depend on Habyarimana. Therefore, to assassinate

Habyarimana, in these conditions, was not in the interest of the RPF’s opponents.

Furthermore, many observers have noted that those so-called “Hutu extremists”, both

civilian and military, were not ready to take power. In fact, the assassination of President

Habyarimana seems to have taken them by surprise, as most of them were seeking refuge

from day one after the assassination. Some went to the French Embassy to be evacuated

overseas, while others chose to hide in their homes under army and police protection,

anxiously waiting for the next news and events highlights. No organized group emerged

to take control of the situation and hence benefit from the sudden power vacuum. It is

apparent that no plan was in place, even though rumors about the President’s

assassination had circulated for sometime before the actual event. Surely, if this group

had orchestrated the assassination, indicators after the event would show a certain level of

preparedness on their part. Instead, all indications point to the fact that they were caught

by surprise.

An objective analysis does not lead one to think that Habyarimana’s closest people, or

Hutus that western media call “extremists”, had any interest to loose a leader who

obviously was in a position to better challenge RPF, and had good chances of winning the

presidential election that was supposed to take place at the end of the transitional period.

No other political figure had emerged as a potential replacement of President Juvenal

Habyarimana in case he disappeared or was prevented from participating in the elections.

There were various political wings among Hutus for whom coming up with a consensus

on one leader was a distant dream. In any case for MRND supporters, Habyarimana was

the charismatic figure with who winning presidential elections was an almost-guaranteed

outcome. No one then could have foreseen any successful short-term political future

without Habyarimana. His relatives and his closest entourage did not have any guarantee

of keeping their power and privileges in case of the President death, or even if one of

their own replaced him. The motive for this group appears to be very flimsy.

The means to organize and conduct this operation also seem to have been limited for this

particular group. The Rwandan army did not have the means to conduct such an

operation. Its key leaders were either killed or out of the country. The Defense Minister,

as well as the bureau chief of the military intelligence, was in Cameroon; the army chief

of staff was on the peace mission trip with the President, and hence perished in the same

crash; the chief of military operations at the army headquarters was on a long term

assignment in Egypt; and the Chief of Staff of the Gendarmerie was himself on vacation.

18 Testimony in the Affair No ICTR-95-I-T, the Prosecutor against Clement Kayishema and Obed

Ruzindana, transcript of November 5, 1998, p. 70

Who could then have prepared this coup of force besides the army and police? No

organized group has shown the capacity in the past for conducting an operation such as

the one that killed Habyarimana.

Also important, in looking at who might be behind the assassination, is the summit that

Habyarimana had attended directly prior to his assassination. The last minute change of

agenda, location and timing are suspicious enough, that one wants to look at who had the

opportunity in this meeting. The group labeled today as Hutu extremists did not have the

control or the means to determine the date or location for the summit, and their

participation in the meeting itself only lasted one day. Also out of the control of the “Hutu

extremists”, was the fact that President Museveni of Uganda, openly allied with the RPF,

influenced the events of the day by arriving late, and slowing down the proceedings. Nor

would they have influenced Tanzania’s President to refuse hospitality to Habyarimana,

and then to seize the two smaller planes traveling with him, and not return them until the

RPF was in power.

Another point that needs to be underlined is the fact that advocates of the

”Hutu extremist” hypothesis do not show how the assassins could have had the technical

expertise required to shoot down the Presidential plane. The missiles that shot down the

plane were unknown to the Rwandan army and none of the military personnel had prior

knowledge of how to manipulate such an arsenal. Needless to say, the civilians were not

capable of conducting that operation. The report of the Mission d’Information

Parlementaire Francaise leads one to believe that there were some missiles found by the

RPF, when they defeated the Rwandan army, that had never been utilized. This implies

that the Rwandan army may have used missiles to shoot down the presidential plane.

However, the mission only speculates from ambiguous, sometimes contradictory

information provided by the French intelligence. No one from Mission d’Information

Parlementaire Francaise has seen those missiles. No personnel from the Rwandan Army

were trained to use these missiles. But detractors of the Rwandan Army and Hutus

opposed to the RPF, affirm that mercenaries may have used these missiles. Findings

show that there is no evidence of the presence of mercenaries in Rwanda. The idea was

brought up by Colette Braeckman19, and has not been taken seriously by objective

observers.

Lastly, it is important to highlight the fact that if this group wanted to assassinate the

President, they would not have had to take such a drastic approach as shooting his plane,

because they were close to him, and had access to him. They could have used many

available opportunities to assassinate him in such a way as to take the RPF by surprise

and prevent them from reacting as quickly to the assassination as they did with his

airplane crash.

19 Colette Braeckman, “Rwanda: Histoire d’un génocide”. Fayard, Paris 1994, pp. 188, 189

It appears clear that no objective element works in favor of the thesis of the assassination

of President Habyarimana by Hutu extremists, either civilian or military. They did not

have a logical motive, they did not have the means, and they did not benefit from the

death of the president.

6.4 The Rwandan Patriotic Front, with assistance from its foreign allies

We have now shown that the assassination was probably not carried out by any of the

first three possible groups listed by the French and the Belgian commissions. This leads

to the last possibility: the RPF. Did they have the motive and the means to carry out such

an act? Did they benefit from the assassination? Is there any evidence that would lead

one to conclude that is was indeed the RPF who shot down the plane? These questions

are crucial when investigating their possible involvement.

6.4.1 Motive:

Some people state that RPF did not have the motive to assassinate Habyarimana because

the Arusha accord was already going to give them a percentage of parliamentary seats

that was highly disproportionate to its national political representation20. However, while

the Arusha accord did give the RPF some power, it did not give them all the power. If the

Arusha accord were allowed to be implemented, the RPF would be virtually guaranteed

that the Tutsi minority would never have a chance to monopolize the political power as it

did before 1959. It is well documented that many among the RPF supporters felt that as

the traditional rulers of Rwanda, they should not settle for power sharing. Their goal was

100% control. Therefore, if Habyarimana has been allowed to complete the transition

period as stated in the Arusha accord, they would never have realized their goal. But if he

were prevented from implementing it, they might have an opportunity. Particularly if he

were prevented in such a way as to disrupt the stability of the country and allow them the

20 Even Alison DesForges, a great supporter of the RPF over the years, has recognized that the RPF

obtained sharing way over its expectations from the Arusha Accord. Testimony of Alison Desforges in the

affair No. ICTR-96-4-T, the Prosecutor against Jean-Paul Akayesu, audience of May 22, 1997, pp.44-45.

According to Guichaoua, the “Arusha Peace Accord…gives to RPF and its allies from inside the country a

preeminence that is not consistent with its political representation on the ground”. Testimony in the Affair

No. ICTR-95-I-T, the Prosecutor against Clement Kayishema and Obed Ruzindana, transcript of November

5, 1998, p. 65

opportunity to gain control. This presents a very strong motive to assassinate the

president21.

Compounding this motivation was the fact that the RPF had worked with other

opposition groups, such as MDR and PL, to gain influence and to control a larger block

of seats in parliament. However, these groups had begun to suspect that they were being

misled, and saw signs which hinted to the real RPF intention: gaining full political power.

These suspicions led to scissions between the RPF and within these opposition parties.

With the assistance of these political parties, the RPF could have controlled 30% of the

seats in parliament, but without them, its influence had greatly waned. This prospect of

loosing control could further have motivated the RPF to make a last desperate grab for

before the Arusha Peace Accord could have fully been implemented.

6.4.2 The plan to remove Habyarimana:

Despite statements to the contrary22, after the signing of the Arusha accord, the RPF

realized that their time was limited, and that they had to move quickly to oust

Habyarimana23. After concluding on the necessity to remove Habyarimana, the RPF

decided on the means to conduct the despicable act. Reliable sources indicate that since

Assassination of Juvenal Habyarimana, President of the Republic of Rwanda

21 People who subscribe to this theory point to indicators of their motivation such as certain written

documents declaring their intention to gain full control, stalling tactics during the transitional process even

though the Arusha accord was favorable to their side, the fact that they continued and even stepped up their

offensive in Northern Rwanda during the transition, and even to the fact that the RPF were strongly

suspected of having been behind the assassination of Burundi’s first Hutu president.

In its October 1st, 1990 attack, it was expecting to conduct a quick war up to Kigali hoping to capture it in

three days. When its troops failed to achieve that goal, on October 30, 1990, it changed its military

strategy, opting for a guerrilla war. But its goal remained the same, which is to take power by force. All

objective observers align their opinions in the belief that the RPF are simply opposed to Hutu control of

power. People such as African Rights, Colette Braekman, Alison DesForges, Andre Guichaoua

acknowledge this fact. The Arusha negotiations appear to have been a diversion to make people believe

that the RPF was in favor of a negotiated peace that was not imposed by arms. It is in this context that Mr.

Guichaoua writes, “…for the RPF, the aim of negotiations was essentially to obtain departure of French

troops and finally, to free up some ground for an eventual military offensive”. Testimony in the Affair No

ICTR-95-I-T, the Prosecutor against Clement Kayishema and Obed Ruzindana, transcripts of November 5,

1998, p.60.

Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza in “Rwanda. Le mythe du génocide tutsi planifié à l’épreuve de la justice

internationale.”. Arusha, October 1998 (unpublished)

22 Testimony of Allison Desforges in front of the TPIR, affair No ICTR No ICTR-96-4-T, the Prosecutor

against Paul Akayesu, transcripts of the audience of 22 May, 1997, p.44

23 The RPF document entitled “Situation Actuelle et Perspectives à court terme” describes the plan to

eliminate Habyarimana in these terms: “The non-respect of the Arusha agreement and the re-composition

of the government by discarding by the military and popular force Habyarimana and his supporters, within

a given time frame not to exceed nine months from the date of the signature of the accord. Redefinition of

the Transition: Organization of elections at the time judged the most suitable by the RPF”.

November 1993, there was a “death squad” in Kigali with instructions to eliminate the

President as well as some high ranking officers and civil servants24.

Four important politicians within the government were assassinated within a few months

of the signing of the Accord25. As well, there were several aborted attempts to assassinate

Habyarimana during this period. These attempts were prevented due to the vigilance of

the Presidential guards. It is apparently after the death squad failed to carry out the

assassination of the President, that the plan to shoot the presidential jet was devised.

6.4.3 The means to shoot the Presidential plane:

On January 5, 1994, intelligence sources received a report that the RPF battalion in

Kigali, due to lack of vigilance by the UN Belgian contingent, had enough reinforcement

personnel in the battalion as well as an arsenal of heavy weapons that far exceeded the

limit agreed upon in the Arusha Accord26. Reports included the existence of a missile

SAM-7 being held by this battalion27. It is also known that the RPF had trained

personnel who had the technical capacity to use missiles28. Finally, they had, through

their unorthodox protests, managed to arrange a flight path that conveniently approached

Kigali by passing a remote hillside.

As well as having the military supplies and technical capabilities, the RPF also had

influence with Uganda’s President Museveni. He was indebted to them for their

assistance in his rise to power, and yet would surely have been uncomfortable with this

foreign military force based on his soil. It was in his interest to return the “favor” and to

24 A message of the RPF, obtained December 28 1993 by the government intelligence service, reported that

“the general objective is to arrest important personalities of the Juvenal [Habyarimana] regime and

physical liquidations of a number of military and civilian authorities, with the date and orders fixed. … the

list of victims will be sent to you later, but the number one is well known!”

25 Some messages obtained by intelligence services in the month of December 1993, and in January 1994,

confirm that the intention of the RPF was to provoke chaos like that of Burundi through a series of

assassinations, including that of President Habyarimana.

26 It was believed that these extra troops and arsenals were smuggled in through the shuttles for supplies in

the North that the RPF had been uncooperative about allowing to be searched. The Colonel Marshall, who

commanded the Belgian contingent of the MINUAR, confirmed the infiltration of the RPF army in the

capital during the course of these shuttles. He told the Commission of Investigation of the Belgian Senate:

“I have always been convinced that, when the RPF wanted to find heating wood in the north, it was to

bring some arms. Everything was tried to control that, but in vain.” Report of the Commission of

Investigation of the Belgian Senate, Annexe 1, p. 197

General Dallaire himself stated: “…my staff and troops were not always 100 percent vigilant”. Proceedings

in Jean-Paul Akayesu trial at ICTR, 25 February, 1998, p.52

27 Mr. Stephen Kapimpina-Katenta-Apuuli, the ambassador of Uganda in Washington, and Innocent

Bisangwa-Mbungiye, private Secretary of President Museveni, were arrested in Orlando, Florida in August

1992, while fraudulently buying missiles for the RPF.

28 The RPF shot down RAF planes on several occasions during the war in the north between 1990 and

1993. A reconnaissance aircraft was shot on October 7, 1990; a type Gazelle helicopter was shot October

23, 1990; a type Ecureuil helicopter was shot on Mrch 13, 1993.

get the RPF out of his own country. Museveni was key in organizing the conference, and

was directly responsible for the late closing. He could easily have deliberately assisted in

the last minute changes of location and in the refusal of Tanzania’s President to grant

Habyarimana hospitality for the night. It is interesting to remember that the day

following the assassination, he implied his involvement by stating publicly; “Something

had to be done”.

Finally, the RPF had a clear plan that night. The RPF headquarters in Mulindi were

informed immediately, almost simultaneously, of Habyarimana’s death. They had extra

troops and ammunitions on hand. The battalion within Kigali and in Northern Rwanda

immediately began an offensive attack. Unlike the Hutu “extremists”, the RPF did not

appear scattered, and taken by surprise. An army with an estimated 20,000 soldiers

moved in with rapid efficiency29. The chaos sparked that night ultimately enabled the

RPF to have an excuse to resume the war.

7. The Investigation

7.1 The Interim Government (April 9, 1994 to July 14, 1994):

From its investiture, the interim government, led by Jean Kambanda, Prime Minister,

contacted UNAMIR insisting on the imperative necessity of conducting an independent

international investigation in order to determine clearly the circumstances surrounding

the shoot down of President Habyarimana’s airplain, which led to the death of two Heads

of state, Juvenal Habyarimana of Rwanda, and Cyprien Ntaryamira of Burundi, as well as

about ten of their close advisers.

The verbal request was followed by a letter dated May 2, 1994, addressed to the Prime

Minister of the Interim Government from General Romeo Dallaire, Commander of the

UNAMIR, confirming the UNAMIR’s disposition to “set up an international Commission

of Inquiry”. In the same letter, Gen. Dallaire asked the Prime Minister to name countries

the Rwandan government would wish to include in that Commission as well as to

eventual modalities. In his letter dated May 7, 1994, the Prime Minister of the Interim

Government replied to General Dallaire to whom he forwarded all the requested

information. This correspondence did not have any follow up.

29 Later on, the RPF tried to justify the war resumption by the necessity to stop the massacres, but in reality,

when the war started anew, there were no massacres except those of the RPF in the buffer zone. Amnesty

International reports: “The information coming (among others), of Rwandese ocular witnesses indicates

that some hundreds, indeed some thousands of civilians not armed and of opponents of the RPF made

prisoners have been summarily executed or killed in a deliberate manner or arbitrary, since the renewed

outbreak of the massacres and of the other acts of violence which the death of the former President Juvenal

Habyarimana, the 6 of April 1994. Numerous homicides are registered in a cycle of arbitrary reprisals

exercised in the North-East of the country, sometimes early before the 6 of April 1994, and targeting

essentially some groups of civilian Hutus”. Rwanda. The Rwandan Patriotic Army Responsible for

Homicides and Disappearances.

It is important to note that without international assistance, the interim government did

not have any experts capable of conducting such investigation. In addition, the inquiry

needed to be independent. Finally, it is worth noting that the RPF suddenly resumed the

war. Therefore it was almost impossible for the Interim Government to conduct even a

preliminary investigation. Only an independent commission with security guarantees

from both warring parties would have been able to conduct such an investigation.

7.2 RPF Government (July 19, 1994 to this day)

Once in power, there was never a move on the part of the RPF to investigate the

assassination of the Presidential jet. They have stated on many occasions that they

believe the culprits are members of the rwandan armed forces (RAF), with the complicity

of Habyarimana’s entourage, being assisted by the French military or mercenaries. One

would assume that if their enemies, the “extremist” Hutus, had done this act, that the RPF

would have been only too eager to uncover evidence to prove their guilt. This would also

justify RPF holding on power without being democratically elected. Instead, when the

new minister of justice (a Hutu), Alphonse-Marie Nkubito, tried to set up an

investigation, he was surprised to find out that the new government was opposed to

investigating the assassination30.

Even if, for the sake of discussion, one admits that the investigation was not a priority for

a government made of people who wanted for a long time to remove President

Habyarimana, it is difficult to understand after five years why no action has been taken

to elucidate the circumstances surrounding the death of the heads of state of two

countries. Instead, high-ranking authorities of the present Rwandan administration have

relentlessly engaged in destroying all evidence of the investigation requested by the

government of Burundi.

When the government of Burundi officially asked the new Rwandan government to

investigate the death of President Cyprien Ntaryamira (who was also on the plane), the

President and Vice-President’s office of the Republic of Rwanda reacted by assigning the

Justice minister, Mr. Nkubito, to send a letter to the special representative of the United

Nations, Mr. Shahiyaar Khan, requesting UN intervention. It appears that the RPF not

only had the means, motive, and opportunity to carry out this assassination, they also

seem to have some motivation for not pushing for an independent inquiry. It should be

noted, that Hutu “extremists” and those close to the former regime, have requested an

Assassination of Juvenal Habyarimana, President of the Republic of Rwanda

30 Mr. Faustin Twagiramungu testified: “Myself, when I was still Prime Minister, raised the question of an

international inquiry on that attempt during the council of Ministers, and the Vice-President and minister of

the defense responded to me that this inquiry was not a priority for the country and that no inquiry of this

kind has been undertaken for the other assassinated Rwandese”. Testimony before the Mission

d’Information Parlementaire Francaise, May 12, 1998

investigation, desiring to be cleared of any involvement in the shooting down of the

President’s plane. These requests have all been turned down31.

7.3 United Nations Organization:

In his letter dated May 2, 1994, General Dallaire gave hope to the Rwandan Interim

Government that an international investigation on the conspiracy against President

Habyarimana’s jet would soon take place. However, the same general refused the offer

made as early as April 7, 1994 for a preliminary investigation. He responded that he

would require an American opinion first.

The hope raised by the May 2 1994 letter has for long since vanished because no

investigation has been set up by the UN. The Security Council, in a limited request, asked

the Secretary General, to “collect all information relevant to the affair by all means 32 at

his disposal.” Nevertheless, despite the reminder, the request was never carried out.

Furthermore, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), set up by the

United Nations on November 8, 1994, has not yet investigated the assassination of

President Habyarimana. Since the president death triggered the chaos that followed, it

would seem crucial to determine who was behind this tragic event that sparked the

horrible violations of the international humanitarian law that this Tribunal has the

mandate to investigate.

7.4 Organization of African Unity (OAU):

The Organization of African Unity, under the leadership of its Secretary General Salim

Ahmed Salim, friend of Uganda’s President Museveni, the most important supporter of

RPF in its war against the former Rwandan government, has supported the Tutsi rebellion

since October 1990. The OAU has never denounced the assassinations of Presidents

Habyarimana of Rwanda and Ntalyamira of Burundi, or even offered its condolences to

their families and to the Interim Government.

The OAU set up a commission to look into the causes and the consequences of the 1994

rwandan tragic events. The commission was headed by the former President of

Botswana M. Keturnile Masire, Chairman of the Commission. The latter declared that the

Assassination of Juvenal Habyarimana, President of the Republic of Rwanda

31 The position of the RPF and Kigali’s authorities has been recently confirmed by Tito Rutaremara,

Member of the Legislative Assembly and RPF extremist ideologist, during the latest commemorative

anniversary of the Tutsi genocide celebrated in Rwanda. His interview appeared in the governmental

newspaper “Imvaho Nshya” No. 1278 of April 5-11, 1999

32 Security Council Resolution 918 of May 17, 1994 asked the Secretary General to: “collect all

information regarding who bears the responsibility of the tragic incident which causes the death the

Presidents of Rwanda and Burundi”

Commission would not change anything which has been said on these events but would

rather draw lessons aimed at avoiding such tragedies in the future. However, it is clear

that this Commission had no intention to investigate the assassination of President

Habyarimana. The Commission did not seem to be interested in the truth which might

have been uncovered by an independent investigation. It appeared to prefer to rely on

accounts made by the supporters of the current government of Rwanda. This leaves the

impression that the OAU wants to cover up a number of identities and countries involved

in this conspiracy.

7.5 The Belgian Government:

One would think that the Belgian government would be interested in this investigation in

order to find proof which refutes the accusations of complicity made by RPF towards

Belgian soldiers who were part of the UNAMIR contingent. However, no official move

has ever been made to remove suspicion of Belgian involvement.

The Commission of the Belgian Senate did not choose to investigate the implication of

Lieutenant Lotin and his team. The latter, as mentioned above, carried out an

unauthorized mission in Kagera National Park, escorting RPF members for a purpose

that has not yet been clarified. This mission happened to return at the same time that the

Presidential jet was shot down, and also happened to be in the location from which the

fatal missile was fired. These coincidences cast a strong shadow of suspicion upon the

Belgian’s involvement. However, the parliamentary commission would not clarify

contradictory information regarding the number of Belgian peacekeepers killed in Camp

Kigali (army barracks) April 7, 1994. Some of the witnesses who appeared before the

Commission mentioned a number of 10, others 11, while others report the accurate figure

of 16 bodies of peacekeepers, including 2 Moroccans, whose autopsies were made in

Nairobi33. Analysts are of the opinion that among the slain peacekeepers were

mercenaries hired to assassinate President Habyarimana. Their identities have never been

disclosed.

Finally, The Commission of Belgian Senate has not explained why there was a C130

Belgian Hercules equipped with an anti-missile warning system34 that followed the

presidential jet on its fatal flight.

7.6 The French Government:

33 Testimony of Father Guy Theunis before the Belgian Parliamentary Commission for Rwanda (COM-R

1-68).

34Report of the Belgian Parliamentary Commission for Rwanda (COM-R 1-63).

France lost three citizens due to the assassination of the President of Rwanda, but seems

to have adopted a “wait and see” attitude. Right after the tragic event, the French army

offered to investigate the downing of the presidential jet but General Dallaire declined

and said that he would refer the matter to the Americans first. However, nothing indicates

that the Government of France ever officially requested that investigation. It appears that

the French government was waiting for the UN initiative. France has not even asked the

Secretary General what steps he has taken to comply with the Security Council

instructions on this matter.

7.7 The American Government:

The American government has not expressed any intention to seek an investigation into

this tragic event. Some analysts imply that the American government was behind the

scenes to prevent any initiative that could lead to an independent investigation of this

matter. These analysts are of the opinion that if the US wanted an investigation, it would

have taken place long time ago, either under the UN or under the auspice of an

independent international commission. Of course, as the only world superpower, the US

could assert great influence on the new government in Kigali to co-operate with an

independent investigation if they chose to do so.

7.8 International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO):

Through the United Nations and UNAMIR, the Interim Government had officially asked

the ICAO to conduct an investigation. This matter was then placed on the agenda of

April 25, 1994 but no investigation was ever initiated35. In its letter dated March 28, 1996

to the Regional Representative of the ICAO, the RPF government has only requested an

inquiry limited to the presidential jet.

The Organization has never shown an interest in this matter, although this event is

covered the IOAC mandate. No information is available that the Organization ever acted

on the RPF government request. One gets the impression that either the IACO does not

want to be involved in such a highly political issue, or that it has been secretly prevented

from taking any action. It therefore appears that all the involved governments were not

interested in the investigation, with the exception of the Interim Government, headed by

Jean Kambanda.

8. Call for an Independent Investigation

8.1 The trigger event of the Rwandan Tragedy:

35 Report of the Mission d’Information Parlementaire Francaise, T I p. 234

Analysts are unanimous in consider the assassination of President Habyarimana to be the

event which sparked the massacres and the resumption of the war.

The UN Special Reporter, René Degni Segui, was the first to mention this in his

preliminary report dated June 28, 1994. This statement was not revised in subsequent

reports36. In its preliminary report, the Special Reporter says; “the accident of April 6,

1994 which killed the President of Republic of Rwanda, Juvenal Habyarimana, seems to

be the immediate cause of painful and dramatic events the country is going through right

now.” Further in the same report, he added; “the attack against the presidential jet has to

be investigated by the Special Reporter as long as there might be collusion between the

assassination instigators and the perpetrators of the massacres”. However, he did not

conduct any investigation before his removal as the UN Special Reporter for Rwanda. He

was reassigned at the insistence of the RPF government that found him too critical.

In their report, the UN experts have also noted that “this catastrophe has triggered

planned violations of human rights…37” They did not make any effort to uncover the

assassins of the Presidents who would therefore be linked to the massacres.

According to Filip Reyntjens “ it was extremely important for us to determine who shot

down the president Habyarimana’s plane that was the spark that set off the flame of

genocide and sent Rwanda spiraling into the whole impasse the country found itself

today.38” According to Guichaoua “…the downing of the presidential jet … is certainly a

decisive action which, from that moment, sparked the next dramatic events as things

unfolded… and I think whoever took the initiative led the country into tragedy ..39”

Other observers think that without President Habyarimana’s assassination, it would have